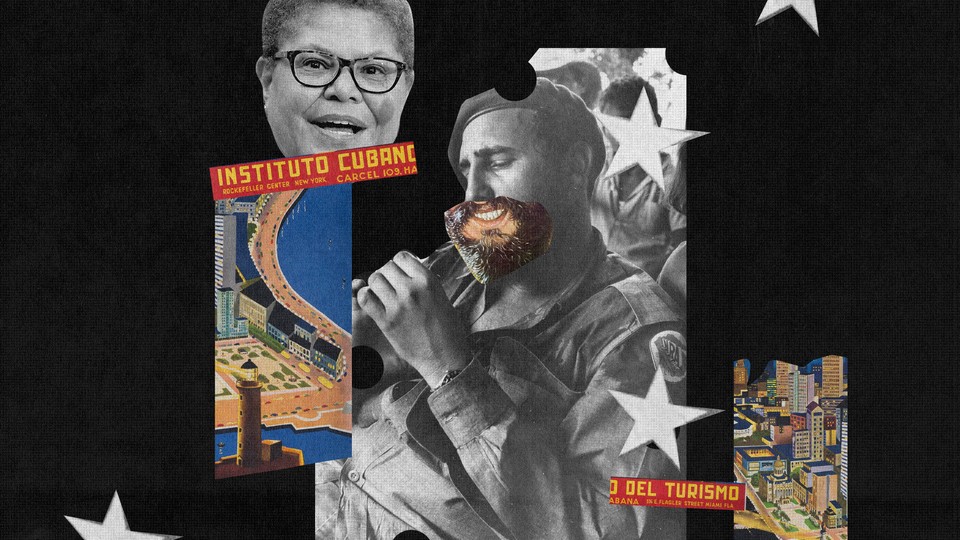

When Karen Bass Went to Work in Castro’s Cuba

In 1973, Bass, who’s now a potential Biden VP pick, traveled to Cuba with the Venceremos Brigade. “I didn’t have any illusions that the people in Cuba had the same freedoms I did,” she said.

Karen Bass, the congresswoman from California, is in contention to become Joe Biden's running mate. There are good reasons for this. She is reliably liberal, she chairs the Congressional Black Caucus, and she shares a history of family loss with Biden. But she’s also the only person on Biden’s list who spent part of the 1970s working construction in Fidel Castro’s Cuba with the Venceremos Brigade, a group that has organized annual trips to Cuba for young, leftist Americans for half a century.

The Biden campaign knows about Bass’s history with the Brigade, which began as a joint venture of the Castro government and Students for a Democratic Society, the leftist, antiwar organization that gave birth to the Weather Underground terrorist group. She told Biden’s vetting committee weeks ago that this was probably going to come up. So far, it hasn’t been a deal breaker—in fact, her potential to drive up African-American votes might help in Florida among voters who traditionally haven’t been paid as much attention in the state.

It’s a reflection of the changing politics around Cuba that Biden would consider a running mate whose past might hurt his chances in Florida, where anti-Castro Cubans are still an important constituency. In 1992, being associated with the Venceremos Brigade was enough to prevent Johnnetta Cole, the then-president of Spelman College who was coordinating education policy for Bill Clinton’s transition team, from being nominated to serve as secretary of education.

Bass recognizes that the issue still matters: When I called last week and told an aide I wanted to talk about her history in Communist Cuba, she quickly scheduled a time to talk. But Bass believes that, in the midst of a pandemic and an economic crisis, many Americans have more pressing concerns than what she did in Cuba 47 years ago. Florida State Senator Annette Taddeo, a Democrat who was born in Colombia but represents a swing district where many Latinos and Cubans live, agrees, but worries that Bass’s spot on the ticket, given her history in Havana, “would be a game changer in Florida, certainly among the Hispanic community.” There’s no question that Democratic Party politics, the resonance of anti-Communism, and Americans’ feelings about Cuba have all evolved since Bass first visited the island. The question now, as Biden makes his choice, is whether they’ve evolved enough to put Bass on the ticket.

“There has been a shift on how to engage with Cuba, but there hasn’t been a shift in Castro’s popularity,” argues Fernand Amandi, a Florida-based Democratic consultant and pollster of Cuban heritage whose past clients include the Obama-Biden campaigns. Referring to comments Senator Bernie Sanders made in March that “it’s unfair to simply say everything is bad” about Castro’s government, Amandi added, “Fairly or unfairly, Karen Bass’s history on this subject makes Bernie Sanders look like Ronald Reagan.”

If Biden picks Bass, he’d be betting that Amandi, and people who agree with him, are overestimating how much voters still care about Castro—and communism.

Bass’s high school in Los Angeles was the kind of place where students were always striking or boycotting something, she told me. Her Spanish teacher, like many of her teachers and other leftist radicals of the ’60s and ’70s, talked warmly about Cuba, where Castro’s revolution was less than two decades old. This wasn’t uncommon: Some Americans on the left, including some Black activists, celebrated the Cuban revolution and the toppling of the Batista government as the end of a racist system. Cuba is “a shining example of hope in our hemisphere,” Stokely Carmichael, the founder of the Black Power movement, said in a 1967 speech in Havana. The best way to think of Bass’s politics at the time—and now—is “as a Black activist who was deeply concerned about what the activists are raising today: systemic racism,” she told me. “I was also deeply concerned on the international front about issues like apartheid in South Africa and supporting the independence movements in Africa. And a lot of times that did not align with U.S. policy.”

It was in this atmosphere, and with Castro scrambling to fulfill a promise of a 10-million-ton sugarcane harvest, that Students for a Democratic Society organized the first Venceremos Brigade. The Cuban government was eager for the help—and especially for the opportunity to bring sympathetic Americans into the country. Venceremos translates to either “we shall overcome” or, perhaps more pointedly, “we shall triumph.” The first group, which called itself an “anti-imperialist education project” to protest the U.S. blockade of Cuba and show solidarity with the revolution, headed to Havana in early 1970. The members of the group, mostly students, lived alongside Cubans, and initially focused on harvesting sugarcane.

Dick Cluster, who traveled to Cuba with the first group but has never met Bass, told me to think about the group in the context of the time, and especially the anti–Vietnam War movement. Young, leftist Americans were suspicious of what they saw as American imperialism. They believed they weren’t being told the whole truth about the world. The impetus for going to Cuba was “let’s go see what it really is,” Cluster said. “And we’re certainly interested in the idea of socialism, since capitalism might be part of the problem.”

The Brigade immediately became a Cold War obsession in Washington, where opposition to Cuba was as much an issue for Democrats as Republicans. The year after the first group returned, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover included the Brigade in his annual report, writing: “Although some of the young people have rejected the communist propaganda and revolutionary philosophy directed against them in Cuba, many of the Brigade members enthusiastically have adopted the anti–United States stance promulgated in Cuba and have aligned themselves with the violence-prone Weathermen and other extremist groups.” Bernardine Dohrn, who led the Weathermen, helped facilitate the first Brigade group’s trip to Cuba. But when I read Hoover’s quote to Bass, she said that she felt like the first part of it applied to her, but the second part didn't apply to anyone she'd met on her trips to the country.

In 1972, a House subcommittee published a report titled “The Theory and Practice of Communism in 1972 (Venceremos Brigade).” In a hearing leading up to the report, Richardson Preyer, a Democratic representative from North Carolina, said he hoped he would learn whether Brigade members were “idealistic, even though misguided, young people who wanted to go down to help with the crops with a regime which they are sympathetic for” or whether they were “interested in sharpening their revolutionary talents and perhaps exporting revolution.” During the hearing, a sheriff’s deputy from New Orleans told the subcommittee that he had infiltrated the group and been subject to extensive questioning and indoctrination sessions. “To be a member of the brigade, you had to be confirmed as a Marxist-Leninist,” he said. The New York Times wrote up his testimony under the headline “Undercover Agent Tells of Cuba Trip With Red Youth Unit.”

After Bass graduated high school, a classmate who had traveled to Cuba with the first Venceremos Brigade connected her with the program, and she decided to go. She was 19 the first time she landed in Havana, in 1973. She remembers spending her time in Cuba building houses—work she compared to that of Habitat for Humanity.

“We built houses during the day,” Bass said, “and then we had what they called cultural activities and we called parties. There was great music, rum, dancing. And we toured the country.” Going to Cuba was a way to meet other young activists, Bass told me. “Obviously, there were Cubans there doing construction work,” she said. “But it was an opportunity for all of the various activists to get together.” She wasn’t the only future politician to join the Venceremos Brigade: Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, a longtime friend of hers, also went.

Bass went to see Castro speak in Revolution Square in Havana, joining “about a bazillion people” in the crowd, she said. Although she couldn’t understand him, he was “extremely charismatic.” She said she was aware then that Cuba under Castro wasn’t the utopia that some of her friends believed it to be. “I know that the crowds cheered, but I have no idea what they were cheering about—and I’m not sure if they didn’t cheer, that wouldn’t have been a problem,” she said. That was the contrast she saw between American activists and Cubans at the time. “I didn’t have any illusions that the people in Cuba had the same freedoms I did. I came home and was protesting everything; I knew that the Cuban people didn’t have the ability to do that.” She didn’t buy the Cuban government’s propaganda, she insisted. I asked whether she knew any American activists who had gotten involved in espionage or violence, and she was firm in her response: “Let me say: Hell no. No, I did not know anybody like that.”

Jeff Schatz, who met Bass on that first trip to Cuba and remains a friend, told me that he remembered her mediating between American volunteers who were getting on each other’s nerves. “She just got in there and worked to say ‘Hey, we’re out here to learn stuff. We’re out here to work and work together,” said Schatz, who added that he fell in love with the construction work he did in Cuba and decided to make a career of it. He now runs a business that specializes in building luxury homes in Malibu.

Two years after Bass’s first trip, the head of the Dade County, Florida, bomb squad testified to the Senate Internal Security Committee that interrogations of members of violent organizations in America had led his group to the Venceremos Brigade. In 1977, the FBI produced a report alleging that some members of the Venceremos Brigade received weapons training. Bass told me she has always rejected violence, and didn’t associate with any militant groups.

“The Weathermen was a white group,” she said. “White, tended to be relatively middle-class folks.” Bass suggested that, for practical reasons rooted in her race, she steered clear of violent activities. “I always viewed that stuff as dangerous, because as a Black woman, I didn’t feel like I could mess around like that. I mean, aside from the fact that I didn’t believe that was going to get anywhere, understand that there was an element of the activism that was scary to me because I was African American and because I was watching all these Black people being killed. I would go to the protest, but when it got to the point of being arrested, that was when I departed. It would have been different if I had been older and in the South and in the civil-rights movement, where there were hundreds of people getting arrested that looked like me. That’s not where I was.”

Bass returned to Cuba without the Brigade in the years that followed, and saw Castro speak several times. She never met him, she said. She was there eight times in the 1970s, and has been back about as many times since. That’s good evidence that she didn’t lead her life focused on building a résumé or trying to rise in politics, she argued. She never hid her association with the Brigade—she gave a “Contemporary Cuban Society” lecture on Valentine’s Day 1977 at UC Santa Barbara (tickets were $1 at the door), for which she was identified as part of the group.

The American government’s interest in the Venceremos Brigade continued for years. In 1982, a Senate Judiciary subcommittee held a hearing featuring a former member of Cuban intelligence who had defected to the United States. He testified that Cuban intelligence had connected with members of the Brigade while they were in the country, and that some Americans had become sources for the Cubans. Bass says she wasn’t involved in anything like that, either.

But Bass was well enough known as a community activist, with a focus on protesting police brutality, that the local government tried to come after her because of her connections to the organization. In 1983, L.A. police chief Daryl Gates tried to link Bass to a gun-running operation, using police reports that said Bass had “returned from Cuba bringing back propaganda literature.” She told police that she had not received any military training while in Cuba, and told me that the police had fixated on her learning to use a gun for target practice during a Brigade camping trip outside L.A. “I’m angry and I’m shocked that they would use [this allegation] to try to attempt to smear me personally and the brigade,” she told the Associated Press at the time. Bass later learned that the person who taught her to use a gun during that camping trip was an undercover police officer. Looking back, she called her questioning by police “absolutely absurd,” telling me, “I never, ever, ever came near a gun in Cuba, period. Never. And frankly, I think if any of that had been true, they would have brought us all in jail.”

Bass’s interest in Cuba kept up after she became a member of the California assembly. She went to the country again in 2005, on a trip organized by the California lobbyist Darius Anderson and paid for out of her campaign account, according to campaign-finance records kept by the California secretary of state. She’s returned several times since being elected to the U.S. House in 2010. She visited Alan Gross, the USAID contractor whom Cuba accused of being a spy, during his five years in prison, and joined then–Secretary of State John Kerry when he went to Havana to raise the American flag over the reestablished U.S. embassy in 2015. President Barack Obama invited Bass—by then a key supporter of normalizing relations with Cuba—to join the presidential delegation during his historic trip in 2016. From there, she tweeted a sepia-toned photo of herself from her Venceremos Brigade trip, in sunglasses with a bandanna on her head.

In Obama’s speech to the Cuban people, he called on them to stop making America a scapegoat for their problems—and on Americans to admit that the embargo didn’t work. Bass said she agrees with Obama’s views. “How long can you have the same policy and not make a difference?” she said. “I thought things needed to change.” She trained as a physician’s assistant, and her interest in Cuba in recent years has focused on medical issues. She and several other members of Congress from underserved, heavily Black districts established a program to send students, particularly Black students, from Los Angeles to Cuba for medical training they wouldn’t otherwise be able to afford. She’s also tried to get California regulations changed to allow Cuban doctors to do their residencies in the state. This, she said, is a natural point of collaboration.

Bass’s affinity for Cuba grows out of a connection she has always seen between the histories of Black Americans and Black Cubans. “The other thing about Cuba, by the way, that has always interested me is that the Cuban people look like me,” she noted.

Cuba has been the main issue that people who don’t want Biden to pick Bass have focused on, mostly because of a statement she made after Castro died in 2016, when she referred to him as “comandante en jefe,” which she says was a poor attempt to translate commander in chief. In Cuba, this was a phrase Castro’s government often used to praise him. When I spoke with her in early July about that statement, she told me that she somehow hadn’t fully realized how Cuba and Castro were seen in Florida, as opposed to California. She told me last week that she’s since reached out to congressional colleagues from Florida, and to Cuban American leaders, to further her understanding of the issue.

“If I had to make that statement over again, I wouldn’t use those words,” she told me, repeating the practiced line she’s been giving in response to questions about the gaffe.

“The idea that this issue is the foremost issue on the minds of people in Florida, when people are dying, when there aren’t [enough] ICU beds—again, I would not make that same statement again,” Bass said, but “it’s hard for me to believe that that is what’s going to be on people’s minds in the next hundred days.”

Bass is right that there are more important issues than what she was doing in Cuba nearly half a century ago, Taddeo, the Florida state senator, told me. “However, Florida is going to be decided by less than 1 percent, and this would be exactly the changing of the subject that we should not change thanks to this emergency that we’re in, because of the leadership of the president and the governor,” she said. “Now we’re going to talk about Cuba? That’s exactly where we do not want to go.”

Roberto Rodriguez Tejera, a Cuban American who hosts a radio show popular with Cuban Americans in Florida, told me by text that he felt sure, given her history, that Bass would take the state off the table for Biden. "It’s not only about Cuba. It’s about the socialist narrative. She is the poster person for it. A dream come true for the Republicans,” he wrote. “It’s also about any independent voter, anywhere in the country, who may be afraid of a total takeover of the Biden presidency by the radical left.”

The Venceremos Brigade, which still exists, and still sends young Americans to Cuba, declined to comment on the record. All told, about 8,000 Americans have traveled to Cuba with the group over the past half century. A trip had been scheduled for July, but was delayed because of the pandemic.